Treating pressure:

Pressure can be manipulated in many different ways: medical, laser or surgical. Surgical intervention can have many guises, including minimally invasive surgery, which tends to be an excellent choice in early disease. Some patients may require filtration surgery, with the traditional technique being trabeculectomy. However, in situations where a trabeculectomy has failed or likely to fail, tube shunt should be considered.

What is a tube?

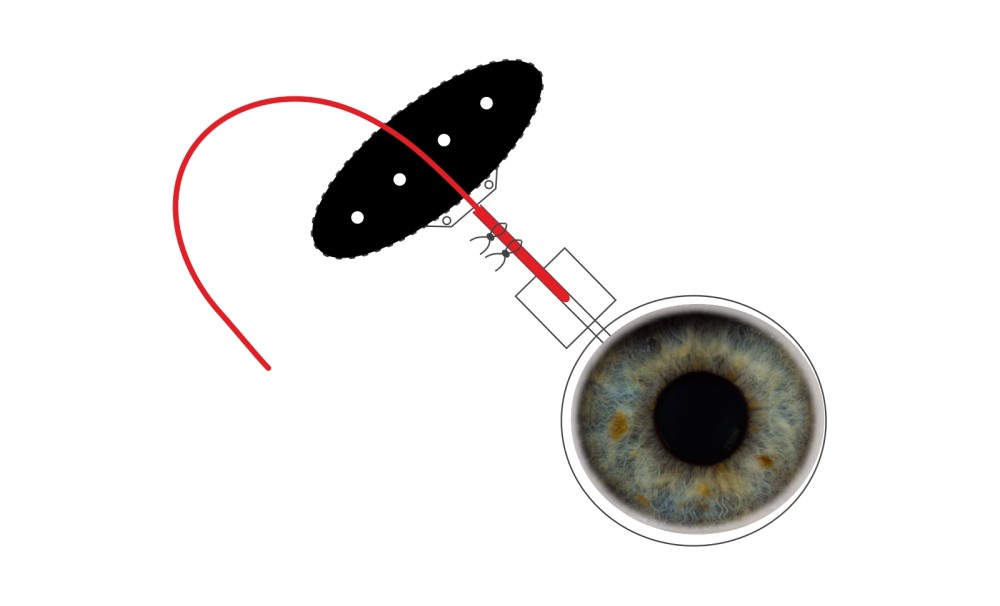

The basic design of every shunt is a silicone tube connecting the interior of the eye to a plate, secured in the space underneath the superficial skin of the eye. Hence it creates a conduit between:

- The inside of the eye

- The surface of the eye

The tube is initially blocked with a large suture inside the hollow lumen: without this the fluid of the eye would ‘gush’ out of the tube, causing the pressure in the eye to go dangerously low. A pressure of less than 5mmHg is called hypotony and occasionally this needs to be treated.

With time, the plate of the tube develops resistance, causing the pressure to go up. Hence around the two-month time frame, the large suture is safely removed in theatre to enable the flow of the tube to be optimal. It is always safer to do remove this ‘tube blocking stitch’ in theatre at approximately two months due to:

- It is a sterile environment, minimising risk of infection

- The position of the tube inside the eye can be safely visualised whilst the internal blocking stitch is removed: this will minimise the risk of the tube itself from moving (retracting)

It can be conceptualised that creating a tract from inside the eye to the surface can potentially cause an entry port for microbes within the ocular surface into the eye. This of course is critical to avoid and is done so by meticulous closure of the ‘skin of the eye’, called the conjunctiva. Hence, once the plate is firmly secured onto the surface of the eye, the following steps are taken to ensure the tube is not exposed or erodes through the surface:

- A barrier is place over the tube

- The most commonly used is called ‘tutoplast’

- This is commercially prepared pericardial tissue, hence rigorous tests are applied to enable use. The only exception to this is prion’s disease, however no cases have been reported in glaucoma surgery.

Where do we put the tube?

Most commonly used are non-valved tubes, enabling fluid to flow freely from inside the eye:

- Baerveldt tube

- Paul tube

Furthermore, choices exist as to where to place the tube inside the eye. Key determinants that modulate the choice of implantation include:

- Space in the eye

- The space between the cornea and lens is called the anterior chamber

- Variability exists as to the space in the anterior chamber

- If there is adequate space, the tube can be implanted here

- If this space is minimal, the cornea/iris is pathological, the view of the front of the eye is compromised, an alternative location to implant should be sought

- Locations can include:

-

- Behind the iris (the ciliary sulcus)

- https://bmcophthalmol.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12886-020-1329-1

- Pars plana

- This of course requires the vitreous humour (‘jelly’) being removed at the time of tube implantation (vitrectomy).

- Note, the human eye does not require the vitreous humour and indeed many instances a vitrectomy is required for various pathologies

- Behind the iris (the ciliary sulcus)

-

- Co-pathology

-

- In situations where there is dual pathology (for instance glaucoma and pathology in the back of the eye), it can be sensible to do combined surgery

- This would be a consideration of a pars plana tube

-

Common indications for tubes

- Failed trabeculectomy

- Situations where a trabeculectomy is likely to fail, the so called ‘secondary glaucoma’s’ including:

- Rubeotic glaucoma (secondary to vascular retinal disease most commonly vein occlusions and diabetic eye disease)

- Traumatic glaucoma

- Glaucoma in the presence of a corneal graft

- Glaucoma secondary to retinal surgery, such as for retinal detachment repair

- Paediatric glaucoma

Common scenarios where a tube may not be sensible

- When general anaesthesia is not an option due to systemic co-morbidities.

- In this situation, a different type of treatment called cyclodiode laser may be an alternative option (see http://www.ophthalmologyinpractice.co.uk/managing-rubeotic-glaucoma-at-the-western-eye-hospital)

- Cyclodiode laser also has risks and benefits, with the decision to proceed with treatment not to be undertaken lightly.

- Whereas tube surgery helps fluid egress out of the eye (thereby reducing the pressure), cyclodiode laser reduces the formation of fluid in the first instance (i.e. reducing the inflow of fluid)

Literature

Amongst other parameters, the AVB study looked at patients undergoing Baerveldt tube surgery. The following results in 114 patients having this type of tube were noted at baseline and at five years:

| Mean pressure (mmHg) | Number of drops | |

| Baseline | 31 | 3.1 |

| Five years | 13.6 | 1.2 |

Post-operative issues encountered included high pressures or low pressures.

An interesting point is raised here which should be emphasised. In other types of glaucoma surgery, the aim is to be without drops (so called complete success). However, with tube surgery this is usually not possible. Drops will be required to work synergistically with the shunt to achieve the desired level of pressure. This expectation of qualified success is important to note and be aware of prior to undertaking surgery.

Gurjeet Jutley

November 2020